BLAKE AND THE STATIONERS

4 AUGUST 2022

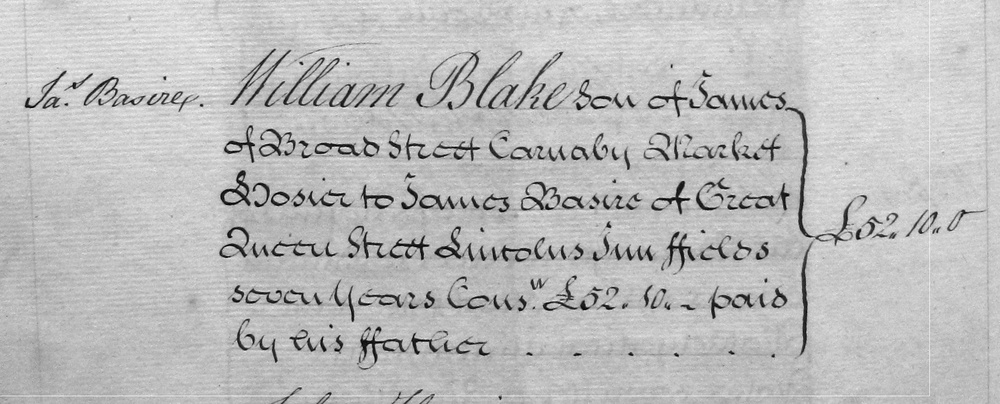

This 4th August 2022 marks 250 years since the apprenticeship of William Blake to Stationer and engraver James Basire. Although Blake chose not to take up the Freedom of the Stationers’ Company himself, this apprenticeship was one of the most significant periods of his life.

For a start, under Basire’s tutelage, the young Blake was exposed to a remarkable range of artistic and intellectual influences. Basire was an established fine-art engraver, and a major contributor of engravings to both the Society of Antiquaries' periodical Archaeologia, and the Royal Society's Philosophical Transactions. Through Basire's appointment as engraver to the Society of Antiquaries, Blake was involved in recording medieval monuments rediscovered in 1775, when the altar of Westminster Abbey was renovated. The Society’s historical collections hold drawings, which, while unsigned, can be attributed to Blake through their dating and provenance; their combination of gothic and neo-classical techniques presage the development of Blake’s highly individual artistic style. These drawings were subsequently engraved to illustrate antiquarian Joseph Ayloffe’s essay ‘An Account of some Ancient Monuments in Westminster Abbey’.

Caption: Countess Aveline tomb, side view; from the Society of Antiquarian’s website https://www.sal.org.uk/collections/explore-our-collections/collections-highlights/william-blake-drawings/

Alongside its importance for Blake’s own artistic development, the apprenticeship with Basire changed Blake’s life by giving him a rewarding professional skill. In eighteenth-century London, the commercial print industry was thriving, not least thanks to the Engraving Copyright Act of 1734 so energetically promoted by Hogarth. From a pool of talented engravers, Blake emerged as one of the greatest. Although his lack of business acumen, devotion to his own artistic process, and prickly temperament combined to keep financial success at bay, his living at least was assured by his print-making abilities.

The liberal book-seller Joseph Johnson was among Blake’s early employers. Johnson made his name as the publisher of such radical writers as William Godwin, Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin. Johnson commissioned Blake to prepare a series of illustrations for a work by another of his protégés, Mary Wollstonecraft. Reproduced below is an engraving for Wollstonecraft's morally instructive narrative for children, Original Stories from Real Life; with Conversations, Calculated to Regulate the Affections, and Form the Mind to Truth and Goodness. (Print held by The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens; reproduced via the William Blake Archive, http://www.blakearchive.org/).

Although Joseph Johnson himself was not a Stationer, he bequeathed his business and shares in publishing consortia to his great nephews John Miles and Rowland Hunter, who were admitted to the Stationers' Company by redemption in 1808. This was the start of a Stationers’ mini-dynasty: John Miles's sons Joseph Johnson Miles and John Miles became Master of the Stationers' Company in 1882 and 1883 respectively. Joseph Johnson Miles’s son John subsequently became Master in 1902.

Another commission from Johnson saw Blake collaborating with John Gabriel Stedman, to create engravings from Stedman’s own illustrations to his book Narrative of a Five Years' Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam. Thanks in part to the energy imparted by Blake’s execution, these prints were frequently used by the anti-slavery movement over the following decades.

Caption: March thro' a swamp or Marsh, in Terra-firma; engraving by Blake, after Stedman. John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative of a Five Years' Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, London, published December 1st 1794, by J. Johnson, St. Paul's Church Yard http://www.blakearchive.org/.

In 1790, Johnson conceived of a new project: the production of a lavishly illustrated edition of Milton’s writings. He was encouraged by the success of a similar venture, the Shakespeare Gallery, published by Stationer John Boydell. Having trained as an engraver, Boydell published some of the most significant prints of his era. He devised his Shakespeare publication as a vehicle for celebrating and invigorating the British art scene, inviting the top engravers of the day to participate. Blake’s own contribution to Boydell’s project was relatively minor, having been invited to engrave a small plate after a painting by Opie when Boydell was dissatisfied with his first choice’s version. However, although Johnson’s Milton Gallery never came to fruition, its subject resonated with Blake, who admired Milton’s art as much as he disagreed with his theology. Over the following years, he composed a series of illustrations to Milton’s writings, both speculative and on commission. The poet inspired Blake to produce an illuminated epic, Milton: A Poem, printed in 1811, and accepted as one of Blake’s greatest works.

Left: Satan Exulting over Eve, 1795. Graphite, pen and black ink, and watercolour over colour print. This image was taken from the Getty Research Institute's Open Content Program, https://www.getty.edu/projects/open-content-program/

Right: Milton in His Old Age, Illustration to Milton's Il Penseroso c. 1816-20 (The Pierpont Morgan Library)

Milton a Poem, c1811. Held at the British Museum (object 6 Bentley & Keynes 4), © The Trustees of the British Museum, downloaded from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Milton_a_Poem_copy_A_c1811_British_Museum_object_6_Bentley_%26_Keynes_4.jpg

Blake continued working, both on his own projects and on commercial commissions, right up until his death in 1827. Below is an engraving from a series of illustrations of the Book of Job commissioned by the landscape and portrait painter John Linnell: the Job illustrations provided Blake with a steady income from 1823 to 1825. But ironically, the source of Blake’s living may also have been the cause of his death: the most detailed analysis of his final symptoms suggests biliary cirrhosis, possibly caused by years of inhaling cupreous fumes while etching.

Caption: Illustrations of the Book of Job invented & engraved by William Blake, engravings on laid India paper 1825. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Edward W. and Julia B. Bodman Collection Downloaded from https://emuseum.huntington.org/objects/30170/illustrations-of-the-book-of-job-invented--engraved-by-will?ctx=30e1e840feb5cf81f60c712bb0b7f80ecbc6f3c3&idx=20 .