JAMES BASIRE

4 AUGUST 2021

This day in the archive: 4th August

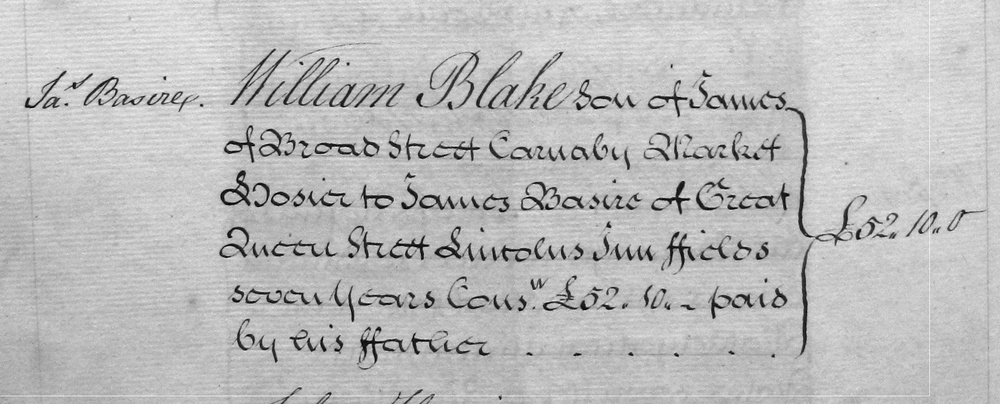

On the 4th of August, 1772, William Blake was bound as an apprentice to the engraver James Basire. Blake, of course, went on to become one of the most important visionary artists and poets in England. Basire's story is less well-known, but as a Stationer, a leading engraver of his day, and a significant early influence on Blake, it's worth telling here.

Main image: William Blake's apprenticeship to James Basire, recorded on 4th August 1772. Apprentice register 1763-1786, Stationers' Company Archive TSC/1/C/05/01/04

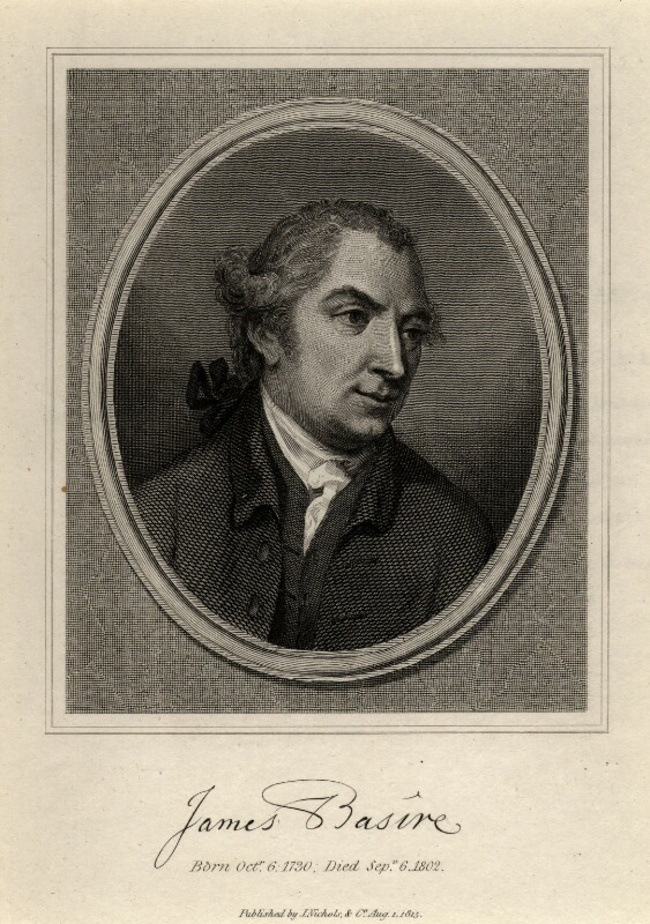

James Basire, published by John Nichols. Line engraving, published 1 August 1815. NPG D1024 © National Portrait Gallery, London

James Basire (1730-1802) was the eldest son of Isaac Basire, a printmaker and draughtsman of Huguenot origin. Isaac was a highly successful printer of trade ephemera, maps and standalone prints. His commercial acumen was at times unscrupulous: in one incident, recorded in 1733, he copied a set of prints from a rival engraver, Henry Fletcher, and then published them for half Fletcher's price. Consequently, Isaac was one of the engravers invited to testify before the House of Commons committee reviewing copyright in engravings. The resulting Engraving Copyright Act 1734, also known as Hogarth's Act due to the artist's energetic lobbying of Parliament, was the first to offer engravers copyright protection for their work.

Antique map of Spain, printed by Isaac Basire, c. 1750. https://www.antique-maps-online.co.uk/spain-basire-2331.html

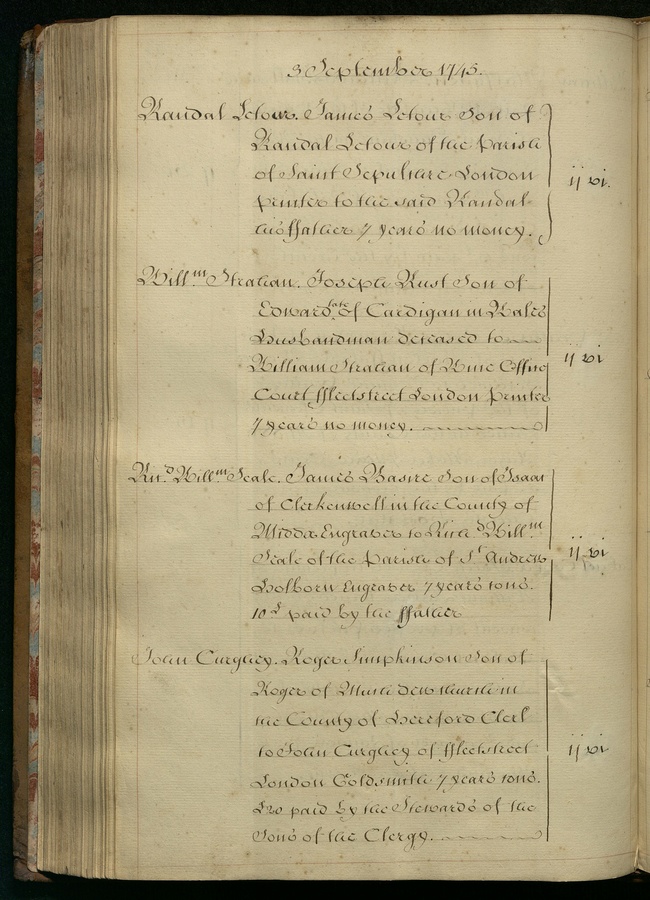

One result of the Statute of Anne was that the 'added value' of high quality illustrations could make a significant difference in sales of competing editions of the same work. Isaac Basire moved into the field of book illustration, working with such leading figures as the French engraver Gravelot and the printer Edward Cave. In 1745, he bound his son James as an apprentice to a Stationer, Richard William Seale. Seale was a line engraver who specialised in maps, a growth area at a time of urban and colonial expansion. (Isaac apprenticed another of his sons, Isaac James Basire, to Stationer William Griffin, a printer and publisher based in Fetter Lane, who published the works of Oliver Goldsmith).

Record of James Basire I's apprenticeship, 1745. Stationers' Company Archive, Apprentice Register 1728-1763, TSC/1/C/05/01/03

Despite the technical emphasis of his education with Seale, James's career took a different path. By the time he completed his apprenticeship 1752 and earned the Freedom of the Stationers' Company, he'd spent part of his term of seven years working with the Limner Richard Dalton, whom he accompanied on a business trip to Rome. Dalton was extremely well-connected, and introduced James to a circle of successful contemporary sculptors, artists and architects. Heavily involved in the foundation of the Royal Academy, and serving as their official antiquary from 1770, Dalton's influence on James's development as an artist-engraver was significant.

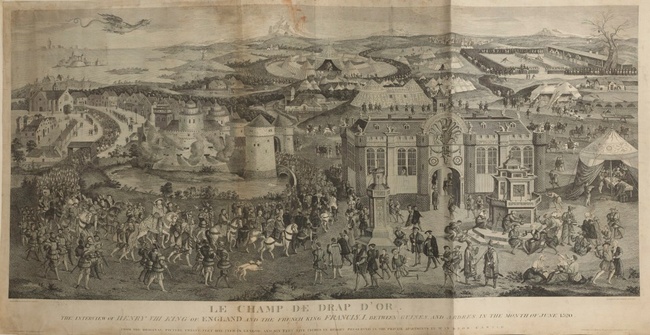

By the time Blake was bound as his apprentice, James Basire had established himself as fine-art engraver, known particularly for the depiction of architectural and historical subjects, and for portraiture. He was a major contributor of engravings to both the Society of Antiquaries' periodical Archaeologia, and the Royal Society's Philosophical Transactions. His book illustrations included work on publications as diverse as Jacob Bryant's New System, or an Analysis of Ancient Mythology (1774), and Cook's Voyage towards the South Pole (1777). He was also renowned for his large-scale engraving of the huge historical painting The Field of the Cloth of Gold, for which the Society of Antiquaries commissioned the esteemed paper-maker James Whatman to produce a new size of paper, the 'antiquarian', which remained the largest paper available for more than a century.

The Field of the Cloth of Gold, engraved by James Basire the elder (1730 - 1802). Original attributed to Edward Edwards ARA (1738 - 1806). From the Royal Academy of Arts Collection

However, it was his appointment as engraver to the Society of Antiquaries which possibly made the greatest impact on his most famous apprentice. Through this connection, Blake was involved in recording medieval monuments rediscovered in 1775, when the altar of Westminster Abbey was renovated. The commission was to have a profound effect on Blake's visual style.

As his business thrived, James Basire was a sought-after master of apprentices, able to provide his pupils with a thorough and wide-ranging training in their art. His two sons, James and Richard Woolett Basire, were apprenticed to him. He also trained his eldest daughter Caroline, whose signature appears on some of the plates she engraved. Caroline's unindentured apprenticeship ended with her marriage, and it was James junior who became his father's business partner, as joint engraver to the Society of Antiquaries, in 1791.

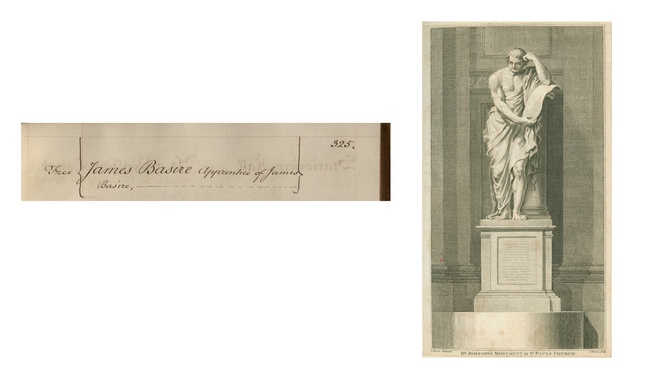

Left: Extract from Court orders recording James Basire II's freedom, March 1791. Stationers' Company Archive, Court book O, TSC/1/B/01/12

Right: Dr Johnson's Monument in St Paul's [Cathedral], after John Bacon RA (1740 - 1799). Engraved by James Basire the younger (1769 - 1835). Published by John Sewell (1734? - 1802) in The European Magazine, 1 April 1796. From the Royal Academy of Arts Collection

James Basire II (1769–1822) was made free of the Stationers' Company on 1 March 1791. He followed his father's footsteps as an antiquarian engraver and illustrator for commercial publishers; he also engraved the Oxford Almanack for the years 1797 to 1809 and 1811 to 1814. As Stationers, the Basires developed close friendships with two other Company dynasties, the Nichols and the Hansards. These personal relationships naturally intersected with professional relationships. John Nichols (1745–1826) was printer to the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries, and subsequent generations of the family were keen antiquarians. The Basires also contributed engravings to the Journal of the House of Commons and other publications of the State Paper Office.

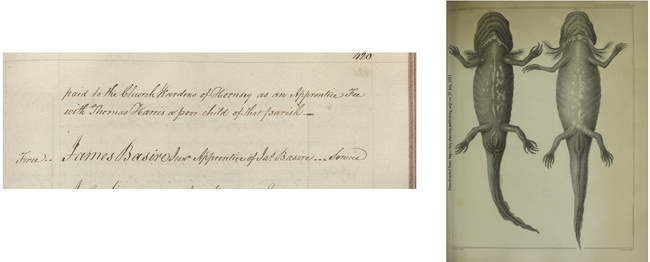

Left: Extract from Court orders recording James Basire III's freedom, July 1817. Stationers' Company Archive, Court book R, TSC/1/B/01/15

Right: Engraving by James Basire III illustrating an article on axolotls by Sir Everard Home in Philosophical Transactions, 1824. Downloaded from https://royalsocietypublishing.org/ on 29 July 2021.

James Basire II's eldest son James (1796–1869) continued the family buisness of engraving, branching out into the new technology of lithography. This cheaper medium was quickly overtaking etching and line engraving as a reprographic technique. The later Basire engravers faced more serious economic challenges than their predessors, in a publishing milieu that was rapidly moving towards a model of low-cost, higher volume print-runs. James Basire III continued to produce work for the Nichols family, particularly illustrations for the Gentleman's Magazine. He and his son James (1822-1883) found an important source of revenue in scientific and technical illustration for works such as the Philosophical Transactions, and the journals of newly-founded specialist societies such as the Royal Astronomical Society and the Zoological Society of London. However, for the last in the line, James Basire IV, engraving could no longer provide a satisfactory living, and, in a move perhaps characteristic of the time, he turned his talents to working on the railway.