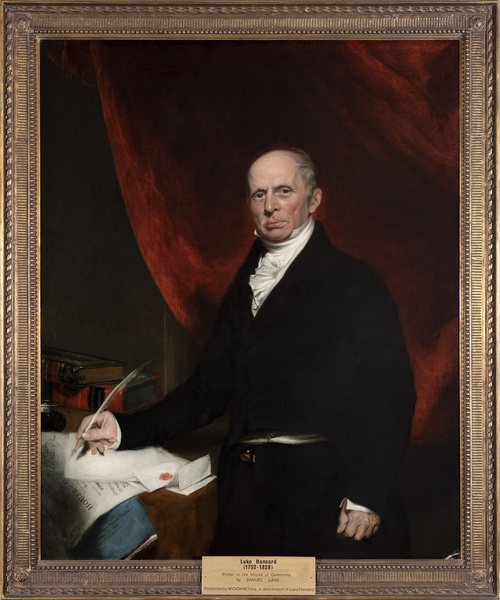

LUKE HANSARD

5 JULY 2021

This day in the archive: 5 July

Luke Hansard, printer to the House of Commons, was born on the 5th July 1752. An exceptionally successful printer who established a thriving family business, he joined the Stationers' Company as a Liveryman in 1799. He endowed two charitable bequests, one for 'needy printers over the age of 65', the other for a 'neatly bound Church of England prayer book' to be given to every youth bound at the hall. He also ensured that all three of his sons were apprenticed through the Company. Two generations later, his grandson, Thomas Curson Hansard II served as Master to the Stationers' Company in 1886. It was Thomas who presented the Company with Samuel Lane's portrait of Luke, which now hangs in the Court Room of Stationers' Hall.

Main image: Portrait of Luke Hansard by Samuel Lane, Stationers' Company collection.

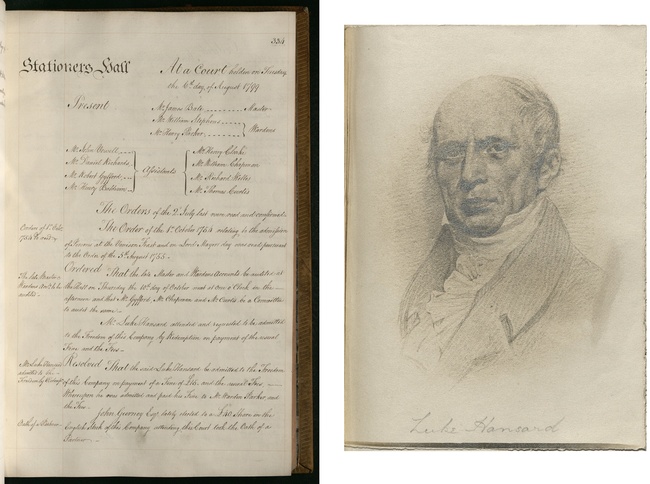

Left: Record of Hansard's admission to the Stationers' Company, 6 August 1799. Court book P, 1794-1803. Stationers' Company Archive, TSC/1/B/01/13

Right: Sketch of Luke Hansard. Beadle's Book, 1709-1973. Stationers' Company Archive, TSC/1/C/01/02

Luke Hansard started working as a compositor for London printer Henry Hughes in 1772. Hughes's business printed for several major booksellers, as well as for the House of Commons, offering Hansard the perfect opportunity to advance his knowledge of both the industry and contemporary affairs. In 1794, Hughes and Hansard went into partnership, and in 1799, Hansard took over the business.

As printer to the Commons, Hansard was responsible for the publication of the Journal of the House of Commons, on which he worked closely with the speaker of the House. Journals have been kept for both Houses of Parliament since the sixteenth century, and are essentially the formal, corrected business minutes of the progress of legislation through the Houses. Through his speed and meticulousness in printing, Hansard secured work from other government departments, and, with his son Luke Graves, he organised and indexed a complete run of sessional papers (this index was eventually published as Catalogue and Breviate of Parliamentary Papers, 1696–1834, and is still in use).

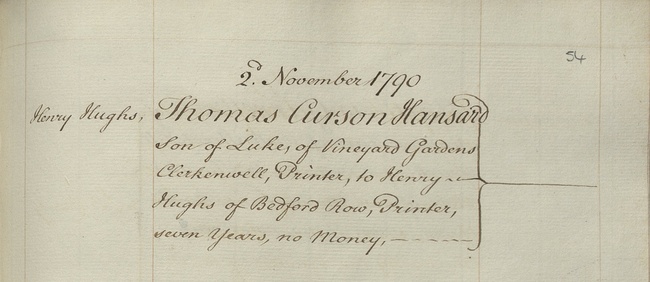

Record of Thomas Hansard's apprenticeship to Henry Hughes, 2 November 1790. Apprentice register 1787-1806. Stationers' Company Archive, TSC/1/C/05/01/05

While Luke Hansard significantly increased the scope and efficiency of his business, it was his eldest son, Thomas Curson Hansard, who contributed to a wider shift in parliamentary printing. Adopting a more radical political position than his father, Thomas left the company of Hughes and Hansard in 1803 and set himself up independently. He undertook printing for the radical political writer William Cobbett, whose ideas he supported, and in 1812 acquired the titles to three of Cobbett's publications: Parliamentary Debates, Parliamentary History, and State Trials.

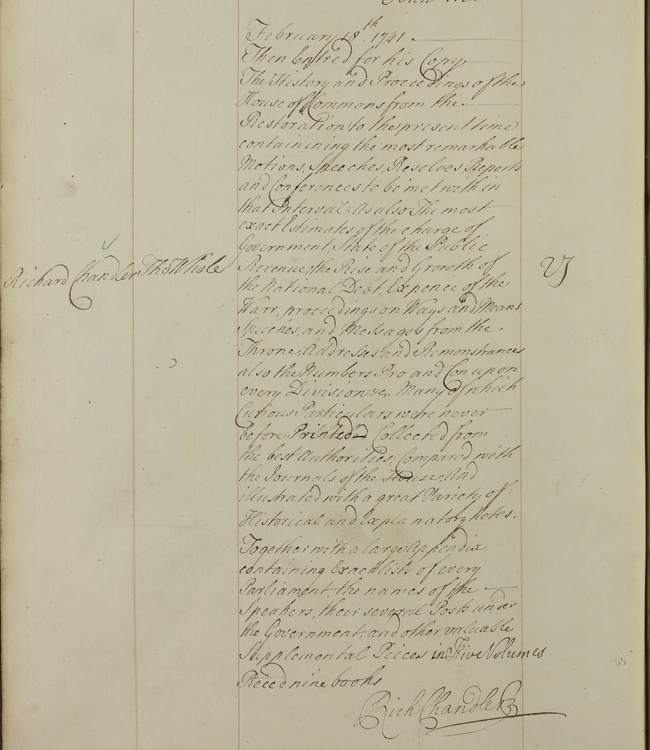

It was the first of these that made Hansard a household name. Reporting of parliamentary debates was traditionally discouraged, and at times legally suppressed. Inevitably accounts emerged, and their were authors prosecuted accordingly. There were some sanctioned publications, of course, mostly historic, such as Richard Chandler's compilation and publication of The History and Proceedings of the House of Commons from the Restoration to the Present Time, registered at the Stationers' Company in 1742.

Register of entries of copies. Stationers' Company Archive, 1710-1746, TSC/1/E/06/08

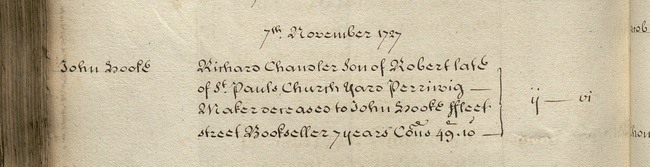

Chandler was an interesting figure: a member of the Barber-Surgeons by patrimony, he served an apprenticeship with Stationer John Hooke, who died before the apprenticeship could be completed.

Apprentice register 1666-1728. Stationers' Company Archive, TSC/1/C/05/01/02

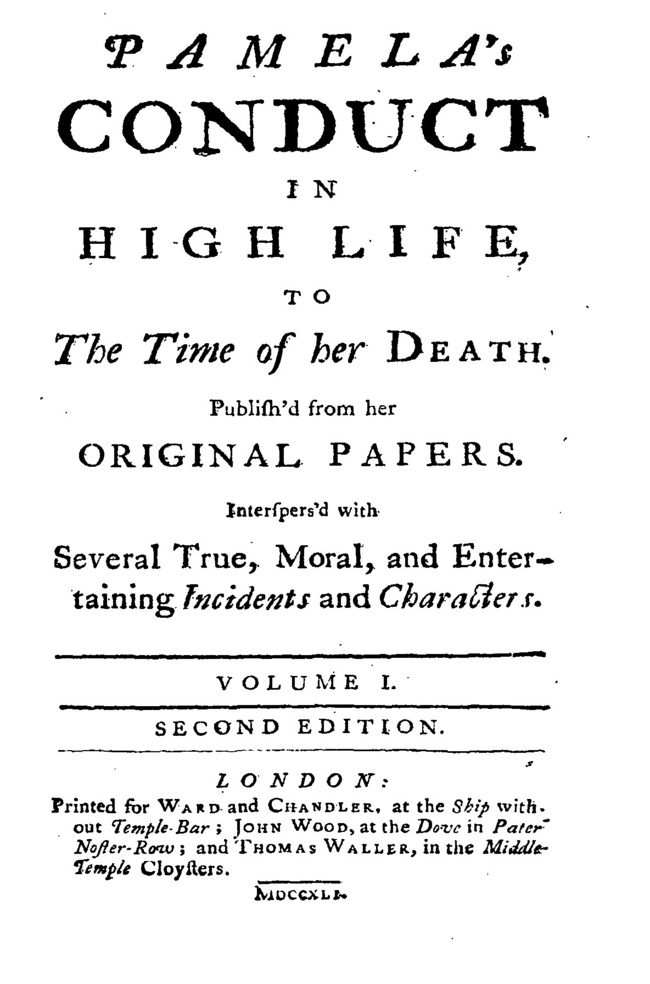

Chandler's entrepeneurial zeal at times took peculiar directions, as when he commissioned a sequel to Samuel Richardson's Pamela, Pamela's Conduct in High Life (1741), without consulting Richardson, and ignoring Richardson's pleas to desist.

Pamela's conduct in high life, to the time of her death. Publish'd from her original papers. ... Volume I. (Volume 1), by John Kelly, printed for Ward and Chandler; John Wood; and Thomas Waller, 1741. British Library; image from EEBO

Sadly, this persistence became Chandler's downfall: despite support for The History and Proceedings of the House of Commons from no less an authority than the Prince of Wales, the publication catastrophically overstretched Chandler's finances. Rather than face debtors' prison, he took his own life in 1744.

The career of Thomas Hansard, who appears to have inherited much of Luke's work ethic, followed a path diametrically different from Chandler's. By the time he took over Cobbett's enterprise, the expansion of newspaper publication in London, and challenges to censorship from politicians such as John Wilkes, had transformed the availability and saleability of direct reporting of Parliamentary debate. Under Hansard, publication of the debates became regular and consistent, and Hansard's publication soon became the recognised standard in the field, and although its format and approach have changed considerably, Hansard's name remains synonymous with the Commons' report.

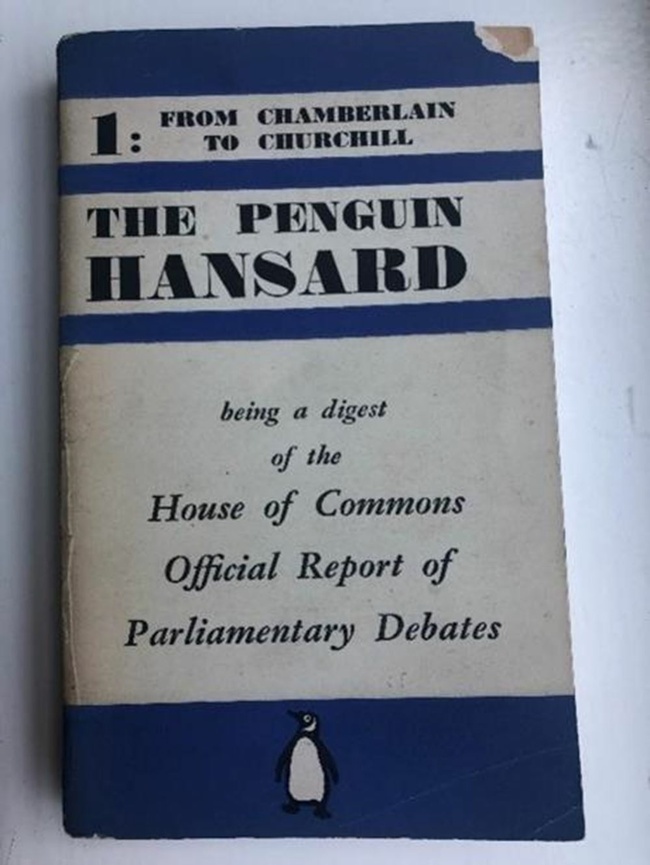

Image taken from https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/private-lives/yourcountry/collections/collections-second-world-war/hansard-ww2/penguin-hansard/

Between 1940 and 1942, Penguin Books attempted to expand the readership of the Parliamentary Debates, hoping to stimulate public interest in politics. The venture proved short-lived, but the spirit of democratising access to the political sphere, which owes so much to the work of the Hansards, is as important today as it ever was.