'STEAL NOT THIS BOOK FOR FEAR OF SHAME': A HIDDEN GEM IN THE STATIONERS' COLLECTIONS

20 MARCH 2024

Postgraduate researcher and archive intern Beth DeBold uncovers one of the treasures of the Stationers' library, an eighteenth century children's book which found its way to the Hall all the way from Cumbria.

The collections at Stationers’ Hall are well known for preserving the historical footprints of the Company, and with them, much of the history of the book trade in early modern England. In addition to Company records, the collection also includes some early printed books; this may be in itself unsurprising for an organisation which has been dedicated to printing and bookselling for over four hundred and fifty years, but there are still surprises to be had.

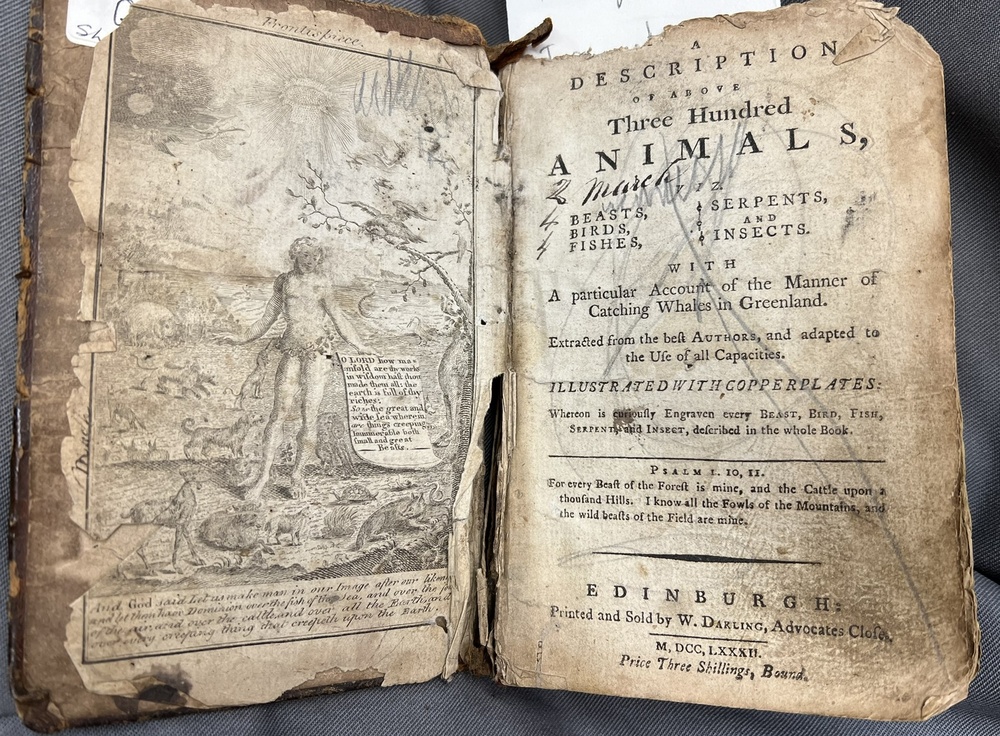

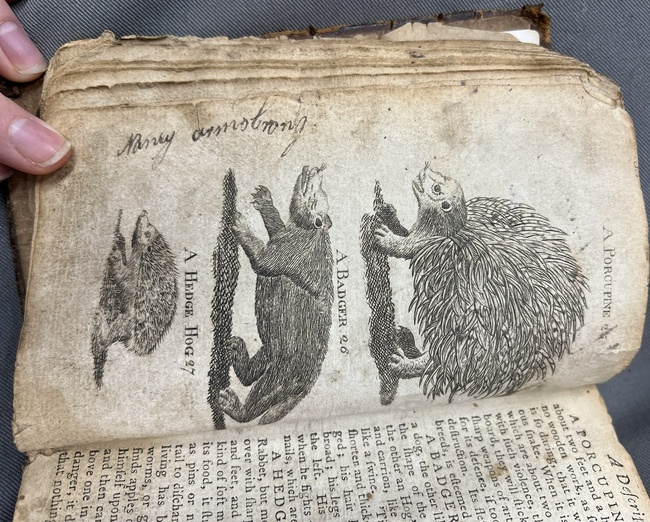

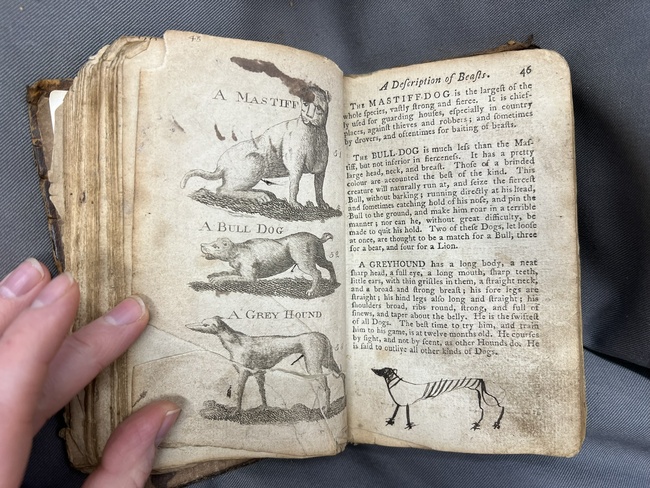

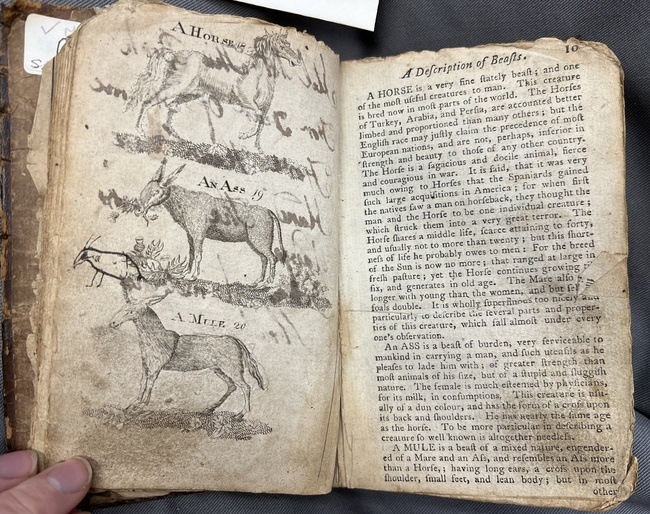

In this case, the surprise is the presence of a small, shabby book printed not in London but in Scotland, with a north-western English provenance, meant for children to read. The book is Thomas Boreman’s A Description of above Three Hundred Animals, printed and sold by the Edinburgh bookseller William Darling around 1782. First appearing in 1730, Boreman’s compendium of animals is famously and fantastically unlimited by reality, including animals such as unicorns, manticores, and dragons. Massively popular, it was printed throughout the century, furnishing thousands of children with educational material filled with pictures.

In a brief introduction to the reader, Boreman writes that his purpose is to engage children by delighting and entertaining them with these pictures and descriptions. In particular, he notes that he has been careful to include “those animals which almost every child is acquainted with.” He might have been pleased to know that the children who owned this copy of his book certainly found it a source for learning, education, and entertainment.

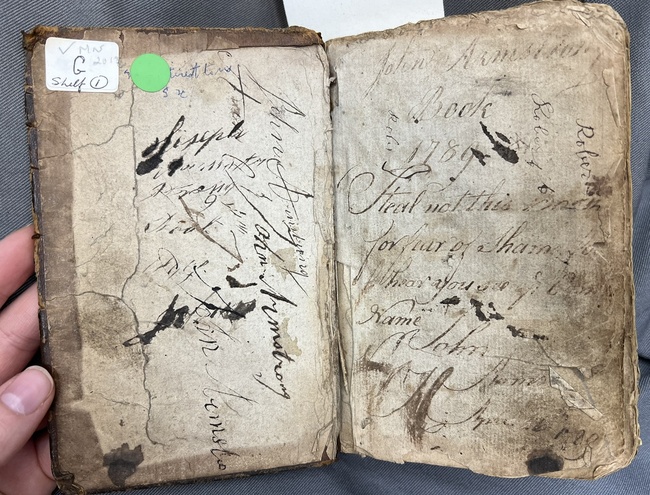

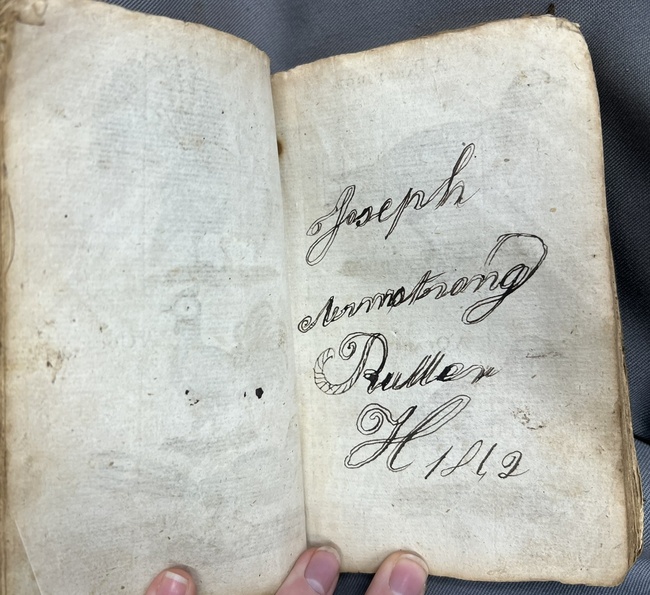

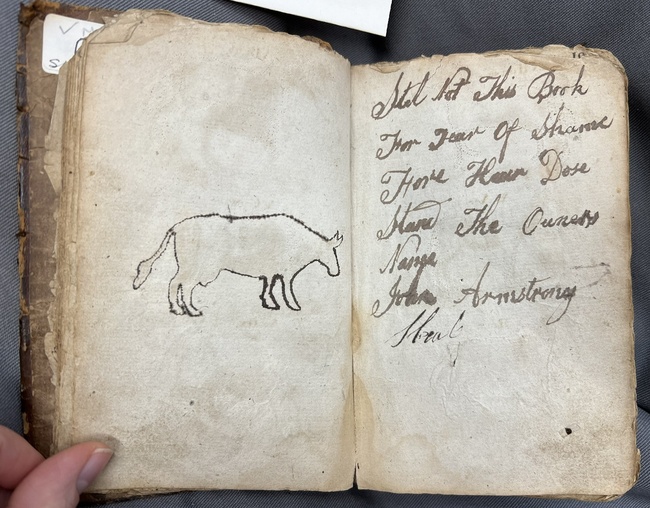

The book has been bound in plain calfskin, likely around the same time it was printed. It has clearly been roughly handled; with the front cover detached, the leather peeling away from the boards, and deep, regular scratching and scribbling on the front and back. The pages inside have also been subject to a litany of abuses: torn, ripped out, dog-eared, softened from many turnings and absorbing the oils from many sticky little hands. Perhaps most interestingly, the book is filled with the names and writing practice of children. Mostly from the Armstrong family of High Rutter in Drybeck, Cumbria (then Westmorland), they have often obligingly included their ages and the dates of their writing, revealing that several generations from this family used and delighted in the blank pages as much as the pictures.

The earliest dated inscription is that of John Armstrong, who wrote his name in 1789, cautioning the reader to “steal not this book for fear of shame, for here you see ye Owners Name.”

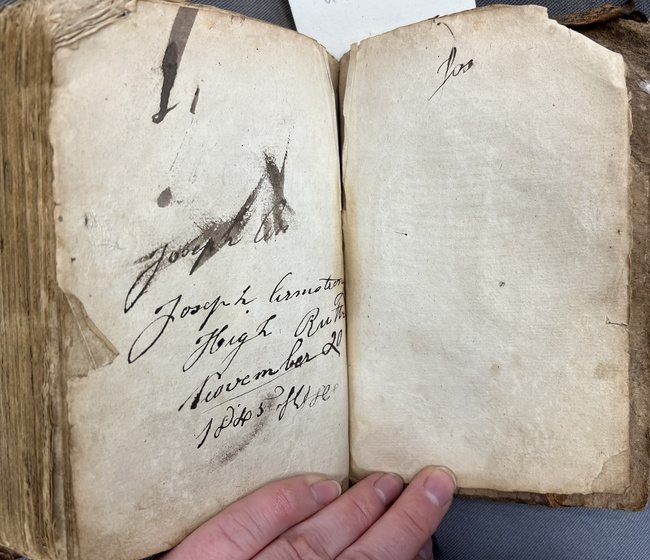

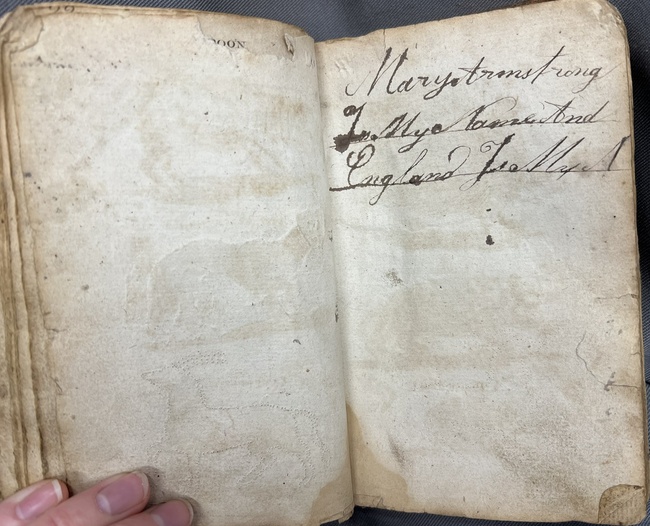

Other names include Peter, William, Mary, Nancy, and Joseph Armstrong, with Joseph and Mary’s contributions being most numerous. Joseph’s entries are often dated in the 1840s, and identify Rutter as his “dwelling place,” while Mary simply gives her age at different points (11 years old). It is telling that the names of both young women and young men appear here, showing that children of all genders were reading and practicing their handwriting in this little book.

|

|

|

|

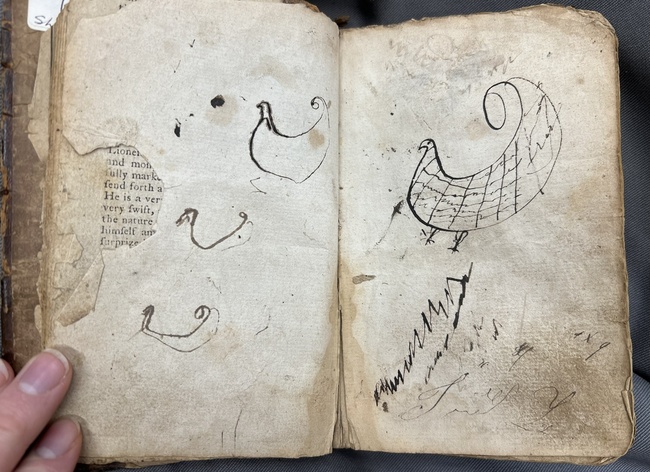

Signatures of Joseph and Mary Armstrong. In the final image here, fine pinpricks in the page facing Mary's signature are evidence of 'pouncing'.

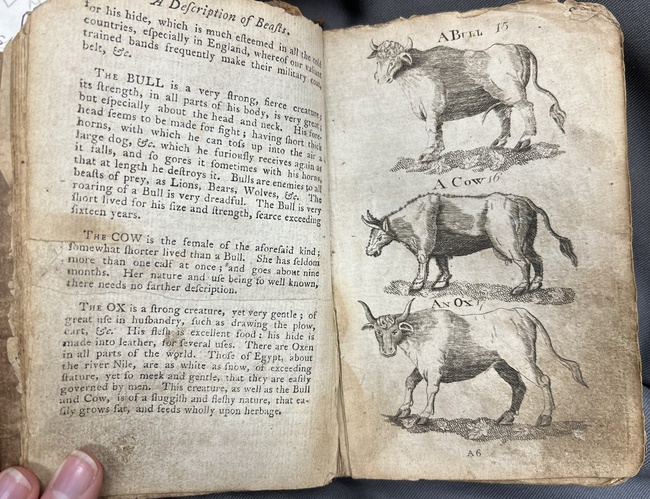

In addition to signing their names, the children were clearly (as Boreman had hoped) engaged with the pictures. Many of the animals show evidence of “pouncing,” where their outlines were pricked with a pin so they could be seen more easily from the other side of the page, to aid in copying the design out or even using it for embroidery patterns. They have often attempted to copy some of the drawings, tracing out cows, dogs, birds, and even a donkey near where the illustrations of these animals appear.

|

|

|

|

Early census records from the 1840s and 1850s place a family with the last name of Armstrong at High Rutter farm in Drybeck in the county of Westmorland, headed at the time the census was first taken in 1841 by a sixty year old man named John, his wife Mary, and their two grandchildren, Mary and Joseph. It seems likely that these are some of the Armstrongs who set their names to the pages. Perhaps the grandfather was the John who signed his name in 1789, then a sprightly ten year old. It is tempting to imagine John’s parents purchasing the book for him, which then passed down through the family, ultimately to his grandchildren Mary and Joseph who set their names to it in the mid-nineteenth century. Although the Armstrongs, and High Rutter, have long since passed away, the long life of this little, tattered book still speaks of their youthful enthusiasms, which still feel familiar today: a love for the natural world, and a fascination with setting pen to paper.

Beth DeBold is a postgraduate researcher in early modern British social history and culture, currently completing an internship placement at the Stationers' Company Archive as part of a Collaborative Doctoral Award project shared between Newcastle University and the Stationers' Company. After a first career in libraries, including curatorial work at the Folger Shakespeare Library, Beth now focuses on the human labour of the book and print trades during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Her doctoral project examines the lives and social networks of Stationers' apprentices who came to London to learn how to make their living at the press or in the bookshop.